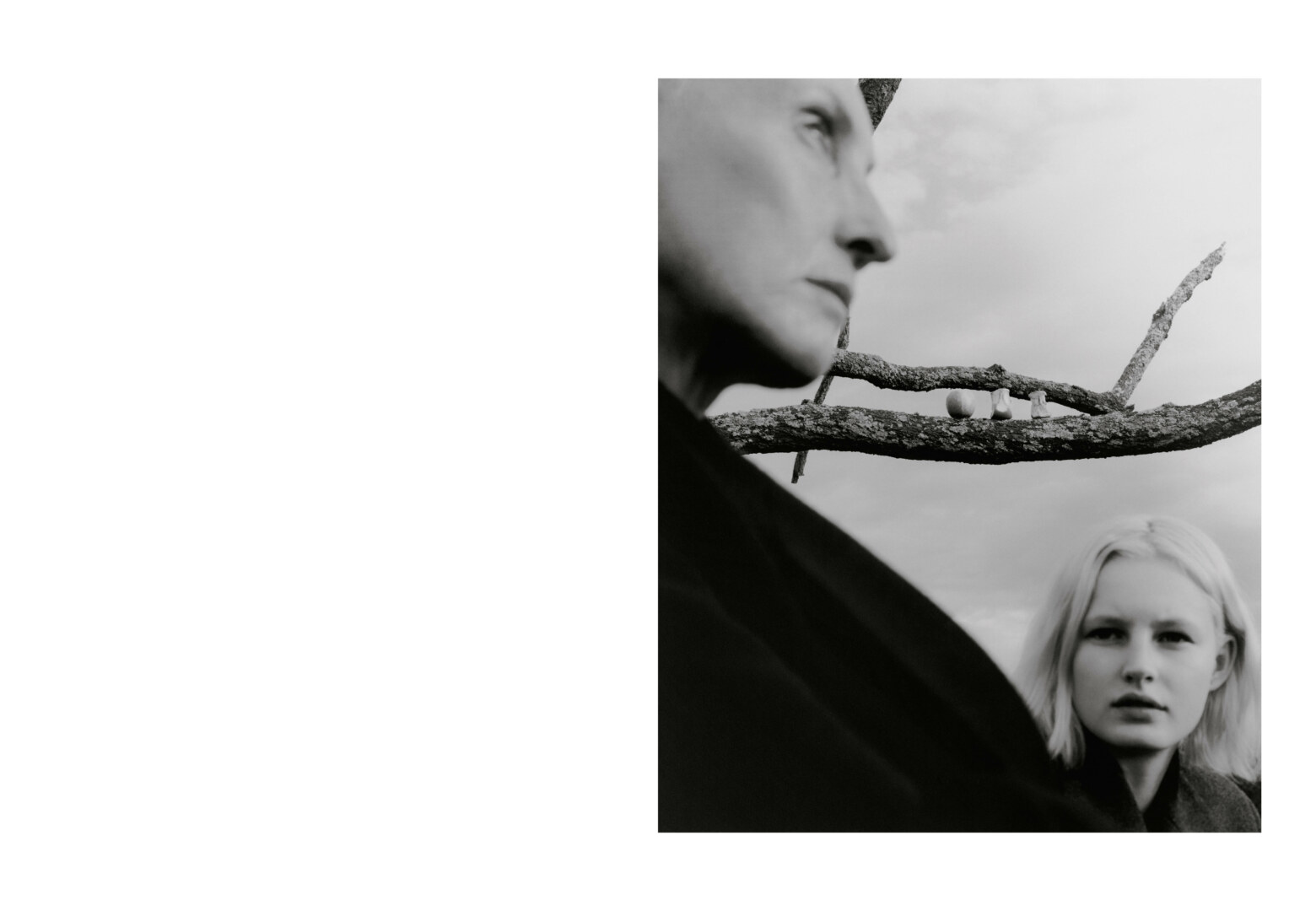

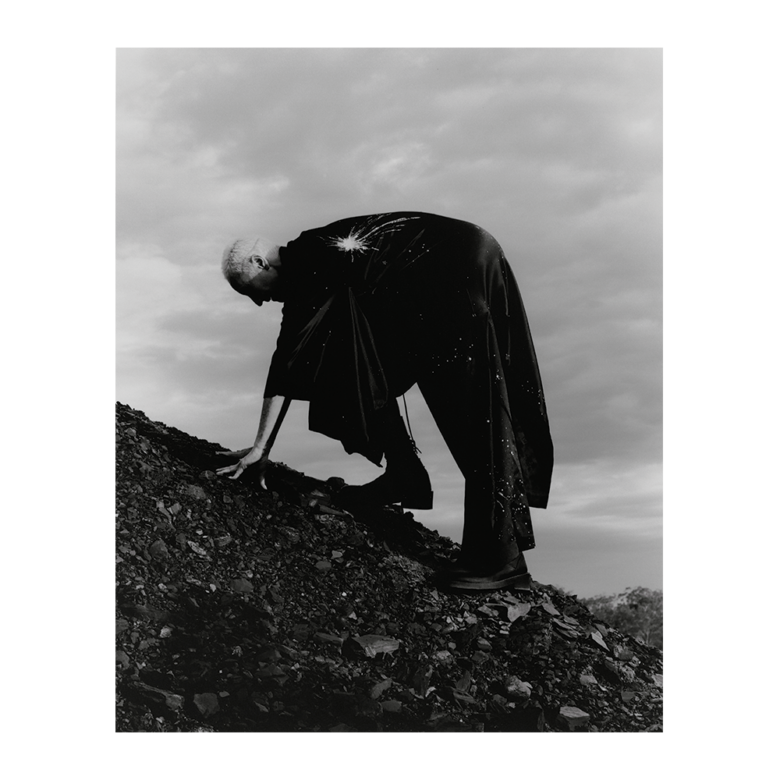

Anthony wears Hermés jacket | Madison wears Michael Lo Sordo jacket | Lenna wears Burberry jacket

THE SPACE BETWEEN BY LEVON BAIRD AND JORDAN WATTON

PHOTOGRAPHER: Levon Baird @ The Artist Group

PHOTOGRAPHERS ASSISTANT: Orson Heidrich

STYLIST: Elle Presbury

CREATIVE DIRECTION/PRODUCTION: Cassandra Wait-Hughes

MAKEUP ARTIST: Claire Thomson

HAIR STYLIST: Rory Rice @ Lion Artist Management

DIRECTOR: Jordan Watton

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Cameron Johnson

CAMERA ASSISTANT: Tahira Donohoe-Bales

WRITTEN BY: Victoria Pearson

DESIGNED BY: Ela Stein

PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS: Julia Corcoran & Alexandra Neville

MODELS: Madison Fanshawe @ IMG | Anthony Smith @ Five Twenty Management | Lenna Holt @ Silver Fox Management

“… please tell us where the slope inclines and can be climbed; for he who best discerns the worth of time is most distressed whenever time is lost.”

When was the last time you reflected on the concept of purgatory? If you closed your eyes and let the word drape across the mind, what image does it conjure? Are you alone, or one of many? Are you ensconced within a structure or idle at the centre of some sprawling terrain?

If we are to use the second instalment of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, ‘Purgatorio’, as a guide, purgatory takes shape as a mountain in the southern hemisphere – a formation that sits between the flames of hell and the gates of heaven. Written in 1320, the narrative poem’s protagonist, Dante, and his guide Virgil must literally scale the mountain; an ascent that is coupled with many lessons and the cleansing of sin, in order to prepare penitent souls for Paradiso.

In more contemporary interpretations of the notion, however, purgatory – or limbo – is seen less as an exercise of physical exertion and more as a waiting room; a place to reside while your fate is being decided upon.

A friend recently described to me their vision of the model: it was impossibly dark, and you couldn’t see your hands in front of your face. You couldn’t make out walls or ceilings, you simply stumbled about in the great black nothingness until someone (or something) called your name.

My personal view, I’ve only recently recognised, is lifted directly from the 1997 children’s film, Toothless. Actress Kirstie Alley stars as an apathetic dentist who, following a freak traffic collision, finds herself dead and stranded in limbo. This middle ground is depicted as a desert vista, dotted with silver trailers and satellite dishes. There is a jaunty track playing in the background upon her arrival, a gothic style ‘Hellevator’ sits ominously to the side, the stairway to heaven is a literal airplane staircase, and a bluebird sky holds nothing more than a menacing sun. If you’d asked me not even a year ago this is exactly how I would have described limbo.

But that was before the Great Pause – before an unforeseen pandemic blanketed the globe and forced us inside to our families and our dogs and our puzzles and our intrusive thoughts. Those previous versions were frivolous, pre-COVID accounts of what it looked like to wait. Otherworldly, full of displaced dirt and butter-thick fog.

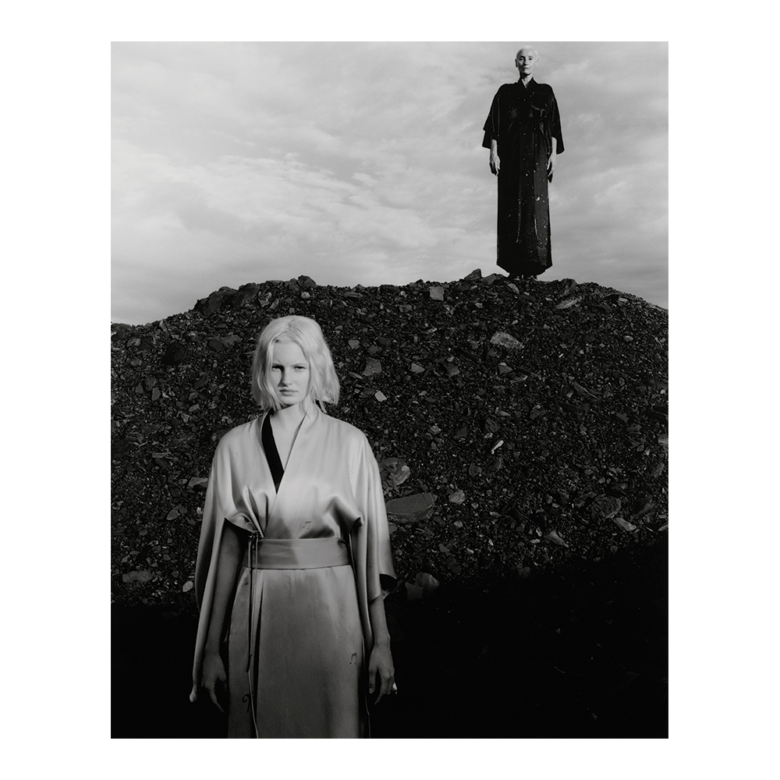

Madison wears Common Hours robe | Lenna wears Common Hours robe

Because limbo has taken on a different tone of late. In fact, upon closer inspection, it looks an awful lot like regular life. We wake up in our own sheets and stare out our kitchen windows and put on our clothes and our shoes and walk along familiar pathways paved upon familiar streets. The only common denominator, it seems, is the waiting. We’re trapped in a period of extended stasis, hoping to be summoned in one direction or another.

How very strange it is; to feel both at home and also stranded.

As a general rule, people don’t love to admit to having their lives meticulously designed. Some baulk at the notion of having a five-year plan. But if we cracked each of us open and muddled around for a few seconds we’d likely find evidence of some kind of projection, or loose framework, for life beyond the present moment.

Have you purchased flights overseas more than a year in advance, for example, or mapped out a rough trajectory of your career, or a promotion you wanted to apply for? Perhaps you know you’d like to own a home, or move cities, or study abroad. I’d argue those are all the bones of a grand plan.

Now, let’s say you are a woman in your 20s or 30s or 40s. It’s probable you’ve dedicated some (or a lot of) mental real estate to that ever-ticking biological clock lurking inside of you. And if you actually want to start a family, it’s equally probable you’ve summoned a number in your head (whether advised or otherwise) and perched it gently on your emotional mantlepiece as the age you want to start, or finish, having children. You’ve estimated the years you have left before surrendering your body and mind to new life and have roughly sketched out the ways in which you’ll spend that time. Again, grand plans.

He answer’d thus: “We have no certain place

Assign’d us”

Lenna wears Christopher Esber jumpsuit

Lenna wears Common Hours robe

It’s amusing, in a way, how little we account for crisis when painting our futures. Considering life’s penchant for throwing shit at the proverbial fan every opportunity it gets you’d think we’d be more comfortable with deviation. But humans have a long and saucy history of digging our heels in when it comes to our constructed realities. We drop anchors and float permanently inside the puddle that best resonates with our mental blueprint for a ‘good’ or ‘right’ life. Whether explicitly or otherwise, we have our futures drafted.

Until a pandemic strikes, and we find ourselves in limbo.

Which is disorientating, isn’t it? The fragility of it all. What feels so certain one day is so volatile the next; we lose jobs, fall ill, miss mortgage repayments, cancel holidays, cancel weddings, cancel birthdays, cancel graduations, lock our doors, don masks, scrap plans, scrap plans, scrap plans. In this communal waiting room, many of our usual barometers for time (life’s major landmarks) are missing, yet of course time still races. Meanwhile change finds us paralysed, unable to make decisions about our futures, therefore making no decisions about our futures.

For perspective, it’s barely been a year. But for perspective, it’s not over. How long do we cling to old futures? How long do we cling to an idea of a life?

The answer, it’s advised, is fleetingly. Dr Elliot D. Cohen surmised it effectively in a 2011 article titled The Fear of Losing Control (penned nine years ago yet pertinent as ever). “The crux of the problem is the demand for certainty in a world that is always tentative and uncertain,” he explains. “It is precisely this unrealistic demand that creates the anxiety. You think that you must accurately predict and manage the future, not just have some probabilistic and uncertain handle on it.”

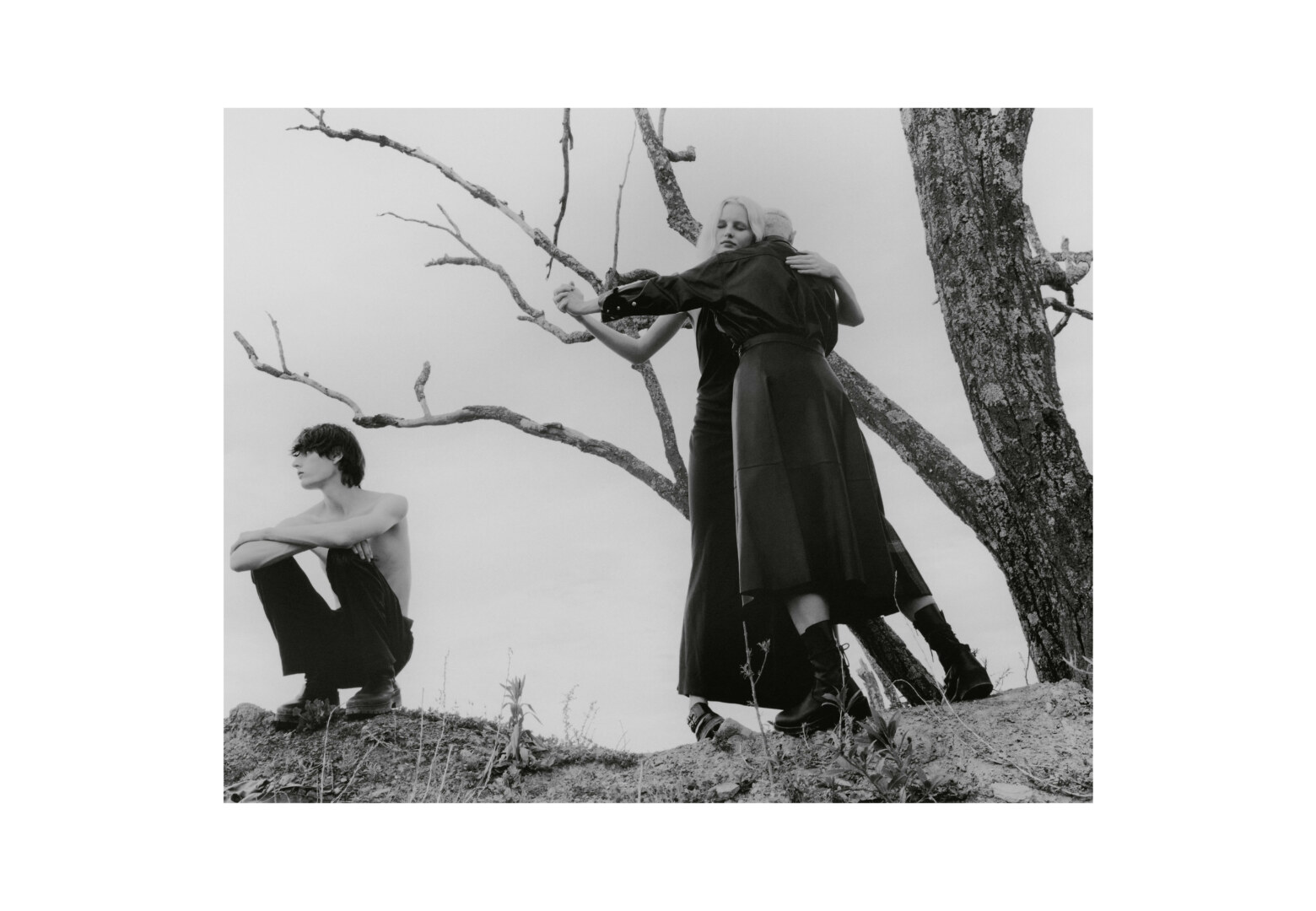

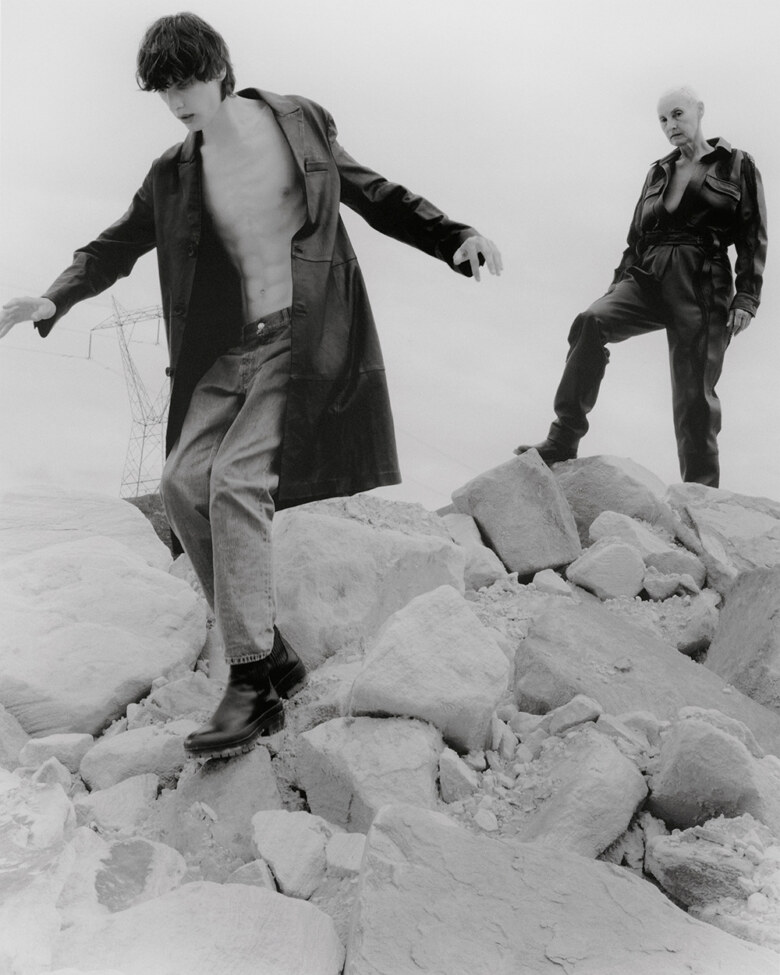

Anthony wears Bally coat and jeans | his own boots | Lenna wears Christopher Esber jumpsuit | her own shoes

A lack of certainty around our futures generates a kind of fear, and it is fear that leads to decision paralysis. So how do we continue to live in such a world without setting up camp permanently in limbo? How do we muster the nerve to put a stake in the ground, or choose a road to follow? How do we construct a life – one that sedates the grief we hold for all that might have been – in this seemingly unending space between?

“… give up demanding certainty,” advises Cohen. Instead, focus efforts on the cultivation of courage. “Attaining serenity is possible only if you face the uncertainty of the

future with courage. This means refusing to cave to the fear of uncertainty, forcing yourself to walk away from your rumination and worry, and to do something constructive with your life,” he says.

“It means having the courage to accept yourself as inherently flawed—as part of a universe that offers no guarantees, and as a being that lives imperfectly in this imperfect universe.”

Wollongong-based clinical psychologist Dr. Nicole Carrigan echoes the sentiment, advising we treat ourselves with gentleness inside these Earth-bound waiting rooms. “Don’t beat yourself up for feeling anxious or try to ‘get rid’ of the feeling – it’s normal and adaptive; we do need some anxiety to motivate us to put in the effort to figure things out,” she explains. “On a practical level, putting pen to paper and writing out pros and cons of different choices can be really beneficial to nutting out our best option.

“At a deeper level: it sounds corny, but speaking to close others (or a therapist) is crucial in coping with decision paralysis. People often say to me “what’s the point in talking about it, only I can make the decision!” That’s true, but there’s something significant about speaking the words aloud to someone else vs. thinking them in your own head. On top of this, when we’re struggling with a choice and feeling anxiety about it, this is a trigger of our very human needs for support and nurturance – needs we can really only get met through connecting with others.”

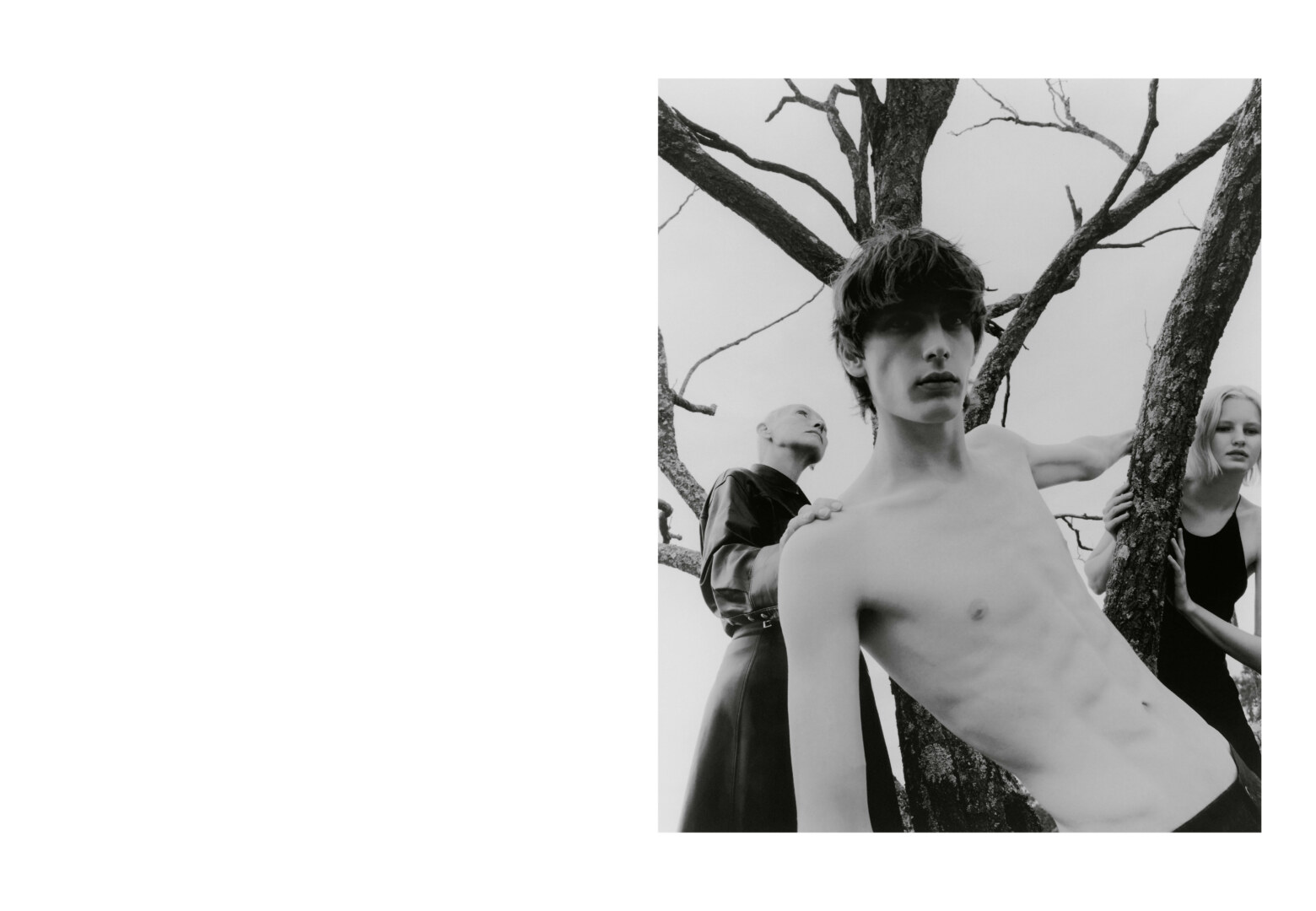

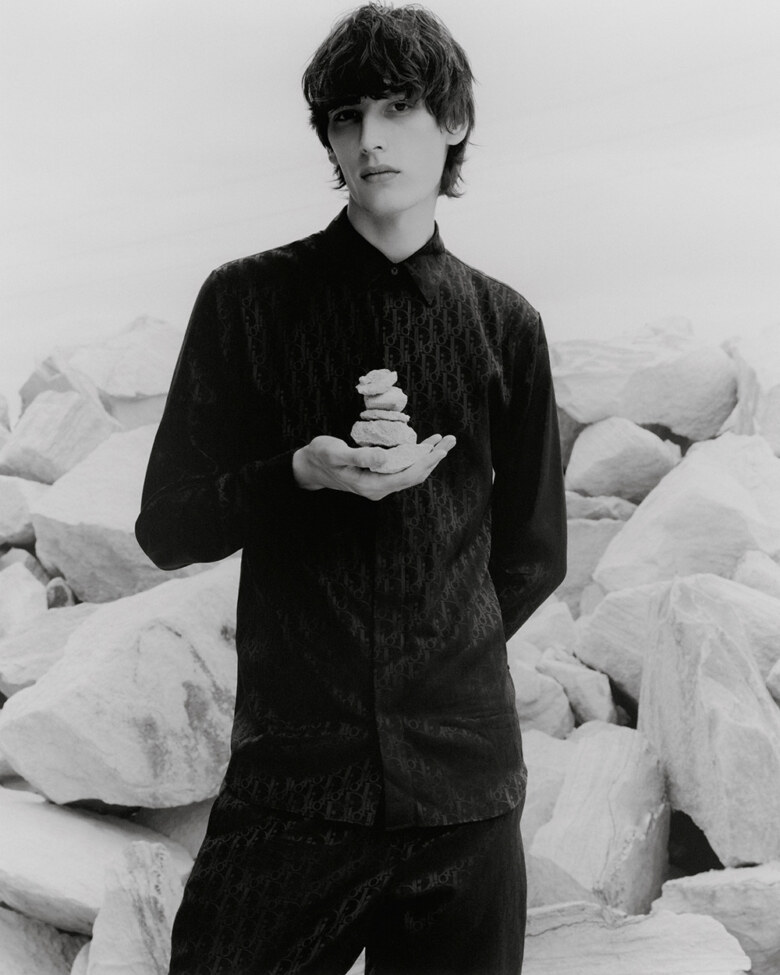

Anthony wears DIOR MEN shirt and pants

In short, we start by acknowledging that we are siblings in these shadows.

Acknowledging that time lurches forward, whether visible or not, and that we’ve got to unstick ourselves and move with it. Acknowledge that these personal purgatories are more or less self-made spaces of self-pity, and that a little self-pity is fine, but limbo can’t be the long game.

Acknowledging that we can’t just rent our lives, we’ve got to invest in them. Even now, when reality doesn’t feel much like a buyer’s market.

Acknowledging that if this is the biggest of our concerns right now – that someone threw a rock into the still lake that was our future – things will probably still work out OK. In fact, the disturbance of the still lake might be the best thing that ever happened to us. “We live with mystery, but we don’t like the feeling. I think we should get used to it,” Mark Strand told The Paris Review in his 1998 Art of Poetry interview. “We feel we have to know what things mean, to be on top of this and that. I don’t think it’s human, you know, to be that competent at life. That attitude is far from poetry.” The takeaway: live like poetry. A bit of (safe and legal) life ruckus keeps us on our toes.

Acknowledging that we aren’t any less for not following our best laid plans; that our best laid plans aren’t mocking us from the sidelines. Our best laid plans might linger in a state of arrested development, but instead of taunting from above they’ll sit frozen behind glass like museum artefacts. Acknowledge that museums are made for passing through. Dwell transiently on your emotional relics, then walk out into the sun.

Acknowledging that our alternative futures won’t be wrong – just different, and that life will continue to grow around them none the wiser. It is as Virgil describes to Dante in Purgatorio of his mission to guide him through hell:

“The only road I could have taken was the road I took”.