DIOR blouse, jumsuit and boots

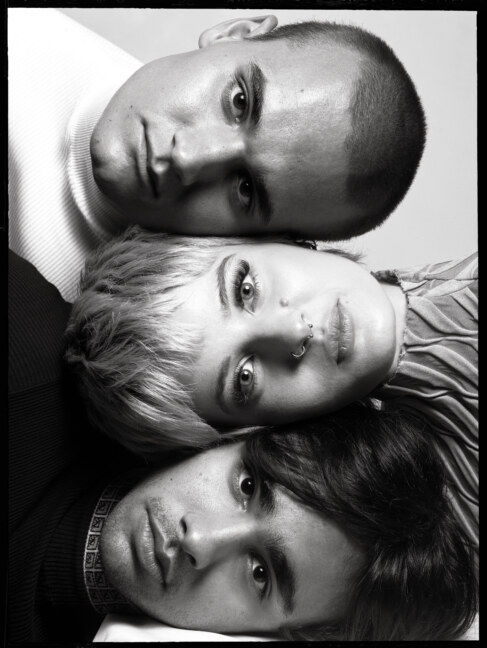

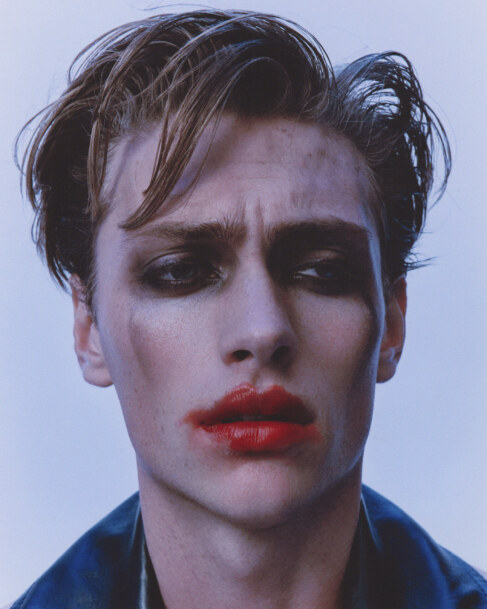

THE SOCIAL DILEMMA – YAN YAN CHAN BY PIERRE TOUSSAINT & GRACE O’NEILL

PHOTOGRAPHER: Pierre Toussaint @ Viviens Creative

STYLIST: Karla Clarke

HAIR & MAKEUP: Samantha P @ Viviens Creative

ART DIRECTION: Stephanie Huxley

WRITTEN BY: Grace O'Neill

Social media gets a bad rap these days. Justifiably so, for anyone who has seen The Social Dilemma and then fallen into a dark hole of existential despair, convinced Facebook is slowly melting our minds and chipping away at the foundations of modern democracy. But our ‘social media = bad’ conversations tend to lack a little nuance. It was social media, for example, that largely facilitated the global civil rights movement that ignited after the murder of George Floyd. For me, a huge amount of the education I garnered on the topic of race was facilitated through my feed – from people like Sophia Roe, Brandon Kyle Goodman, Zeba Blay and Aja Barber, none of whom I would have found were it not for forwarded DMs and handle tags on Stories.

During the pandemic our lives shifted almost entirely online, and with most people at a loss as to when they will next physically see loved ones, technology has become more of an essential service than ever before. Yan Yan Chan, one of Australia’s most revered social influencers, has seen her relationship with social media change more dramatically than most. “To tell you the truth, I’ve always been apprehensive about sharing anything that’s too opinionated, or about being vocal online,” she says. “It always felt like such a small or insignificant act, but in the last six months – first with the bushfires, and now with Black Lives Matter – I’ve realized that revolutions happen when millions of small acts happen at once. I now consider it a responsibility to use my voice online.”

DIOR dress and boots

DIOR jacket

DIOR dress

Chan’s views echo the same paradox that many of us internet-dwellers – even those without 180,000 dedicated followers – find ourselves in: Where to tow the line between empty virtue signaling (we won’t go there with the black squares) and squandering the power that digital influence affords you? The question becomes harder – or maybe, perversely, easier – when your audience is largely Gen Z, who expects political engagement and moral transparency from the people they follow.

“It was really surprising, once I decided to start speaking out, to see how many people of colour – many who were much younger than me – reached out with messages of support,” says Chan. “It’s surprising to me that I could have the power to instigate someone changing their perceptions on a topic over something as simple as a social media post – but that’s exactly what happened, and it confirms to me how important it is to keep having difficult conversations, both online and offline.”

It’s easy to agree with the sentiment that people should ‘use their platform for good’, but how this plays out in practice is often complicated and murky. There is line touted on the internet about the importance of ‘letting people learn’, but it’s a motto we rarely see play out in real life. As this new wave of Black Lives Matter support reached fever pitch, a reckoning was taking place in the fashion industry. Brands and publications that had failed to meaningfully engage in inclusion and representation were named and shamed. CEOs stepped down, and the feed filled with Notes App apologies from those promising to “do the work”.

Much of this change was both justified long overdue, but along the way there were occasional slips where a kind of collective bloodlust kicked in – first it wasn’t enough to apologise, and then it wasn’t enough to resign. People began to ‘de-platform’ themselves, and we watched a culture – a culture that was scared, angry, bored and trapped inside – begin to actively seek out wrongdoers and then refuse to give them the opportunity to atone. I watched a lot of this and often questioned how much of what I was seeing constituted tangible progress – and on some occasions I worried that we were actually disincentivizing the growth we said we wanted.

As a person whose career is largely facilitated through Instagram, Yan is grappling with the same questions. On the topic of fashion, for instance, she tries to align herself with brands she respects. She is a long-time collaborator of Dior, who under creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri has promoted an outwardly feminist agenda and embraced the need for more sustainable industry practices in the last four years. But being an entirely ethical creator or consumer of fashion is a tricky – some may say impossible – task. Tripping up is inevitable. Does she think her audience will give her the room to learn as she goes?

“I have been pretty open about the fact that I am still navigating the shift in fashion, in terms of how I stand with sustainability,” she says. “It’s actually been really nice to have the back and forth conversation with people about how to do better. It helps me to share resources and turns it into a journey that everyone is taking part in together, rather than me telling people what they should be doing.” As far as sensible ethoses for navigating the internet in 2020 go, this seems as sensible as any.

–

SIDE-NOTE acknowledges the Eora people as the traditional custodians of the land on which this project was produced. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reading this.

DIOR jacket, pants, tee shirt and boots

DIOR jumpsuit and blouse

DIOR necklace

DIOR jumpsuit