WRITTEN BY: Isabelle Truman

For the past month, Sarah Everard’s death has been headline news. Not just in London, where she lived, but all around the world. Though the story is undeniably tragic—a young woman walking home whose life was ended because a man decided it so—so too are the deaths of at least 207 other women who died at the hands of men in the UK in 2020. So too are the deaths of two women a week who are killed by a current or former partner in England and Wales alone, and the one woman killed each week in Australia in the same way. So too are the deaths of two Black women, sisters Nicole Smallman, 27, and Bibaa Henry, 46, who were murdered last June while celebrating Henry’s birthday with a picnic in a London park, close to where I live, in the middle of summer.

When Nicole and Bibaa were reported missing, their case didn’t make the rounds on social media as Sarah’s did—shared even by friends of mine who live in Australia. In fact, police were so slow to investigate that the two women’s bodies were discovered by their friends, who started their own search party in lieu of help from authorities. When police arrived at the scene, two officers took selfies with Nicole and Bibaa’s bodies, which they then shared on WhatsApp.

Just as Sarah was doing something routine—walking home from a friends, Nicole and Bibaa were sitting together in a park during lockdown, something I and every person I know did religiously during summer weekends in the city. Sarah was murdered by an off-duty police officer, while two on-duty officers stood over Nicole and Bibaa’s bodies to take photos. Both cases are devastating. So why did only one send shockwaves to the farthest corners of the world? Why did only one have a virgil attended by thousands, including the Duchess of Cambridge Kate Middleton? What makes one tragedy capture the public’s attention in a way others do not?

Nicole and Bibaa’s mother, Mina Smallman, has no doubt as to the reason authorities didn’t take her daughters’ disappearance seriously. “I knew instantly why they didn’t care,” she told BBC at the time. “They didn’t care because they looked at my daughter’s address and thought they knew who she was. A Black woman who lives on a council estate.”

The way we view and respond to cases is overwhelmingly influenced by the way the story is told to us through media and the language used to describe the occurrence. Though there have been steps towards changing the way we talk about violence against women—even this description, which fails to put onus on who’s behind the violence, is being evaluated—and the way it is reported on, too often media still focuses on people whose cases readers can immediately relate to. Those whose experiences differ from ours—people whose experiences are marginalised from the mainstream through embedded inequality—are repeatedly overlooked.

When these cases are focused on, often it’s for aspects of the victims’ lives which feed into the narrative that their actions played a part in the violence brought upon them. Such as the murder or rape of a sex worker. On the Instagram account @FixedItHeadline, journalist Jane Gilmore pushes back against the media’s constant erasure of violent men by crossing out harmful, victim-blaming headlines and rephrasing them. Her most recent post at the time of writing is the correction of the Sydney Morning Herald headline, ‘Labour MP says a NSW government MP raped female sex worker’. With a simple red font, Gilmore changed the sentence to read, ‘Labour MP says a NSW government MP raped woman.’ As Gilmore succinctly explained in the accompanying caption, “She’s a woman. Her job is not relevant to rape allegations.”

Focusing the headline on the victim being a sex worker insinuates she ‘had it coming’ due to her dangerous occupation. What we don’t ever focus on is why being a sex worker is dangerous in the first place. As Sally Tonkin, then-CEO of Gatehouse, a drop-in centre for sex workers in St Kilda, Melbourne, said in her 2015 Ted Talk, sex work is dangerous not because women work with heavy machinery, dangerous chemicals or come face to face with wild animals daily. Sex work is dangerous because women are working with men. Sex workers lives are at risk because of their proximity to men who live in our communities. Why are their jobs thought of as the problem, rather than the men who use their jobs as an opportunity to cause harm?

Sarah’s family didn’t have to worry about these headlines. She was white, middle-class and behaving in a socially-acceptable way. Her case, like Jill Meagher’s 2012 murder in Melbourne, was fronted by a beautiful, young, white woman. It was all too easy for the media to use wholesome photos of her smiling at the camera to remind us it could be any of us. Victim-blaming headlines focused on her daring to be out after dark—a fact which prompted police to advise women in the area to not leave their houses after sunset alone, and many more Twitter suggestions for how women could make themselves safe than there were for how men could stop murdering women. But otherwise, she was the perfect victim.

“For millennia, women have been divided into ‘good women’—wifes and mothers, sweetly, prettily, conservatively dressed nice girls, and ‘bad women’—sirens and sex workers, drug addicts, page three girls and drunken promiscuous sluts. Good women are helpless victims, but bad women ask for trouble,” Gilmore writes in the introduction to her book, Fixed It.

After Brock Turner sexually assaulted Chanel Miller on campus at Stanford University in 2015, the media focused on Turner’s promising future and his success as a swimmer, rather than on the heinous crime he had been found guilty of committing. In 2016, when he was released from jail after serving just three out of the six months he was sentenced to, headlines referred to him as a ‘Stanford swimmer,’ instead of a convicted rapist. TIME didn’t bother noting Tuner had committed a sexual assault at all until the third line of their story. Throughout, the magazine referred to him as a “former Stanford student and star swimmer.”

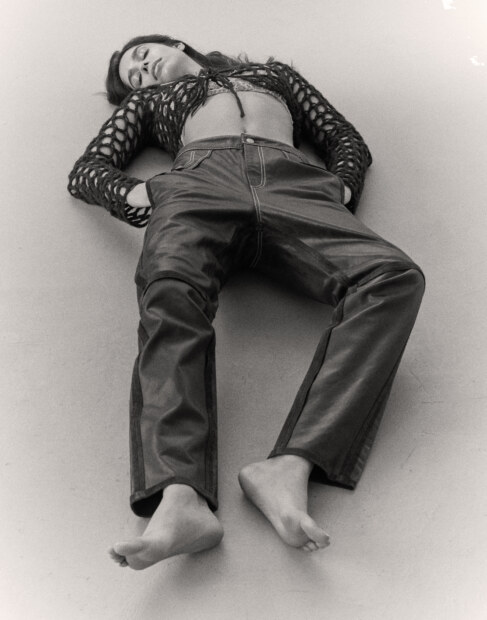

Miller has since released a book, Know My Name, but it was her victim-impact statement, which she read in a courtroom directly to Turner, that still makes the hairs stand up on my neck. “In newspapers, my name was ‘unconscious intoxicated woman,’ 10 syllables, and nothing more than that,” she said. “For a while, I believed that that was all I was. I had to force myself to relearn my real name, my identity. To relearn that this is not all that I am.”

Because of the language used in the media, which filters into our subconscious, women are made to believe we are somehow at fault. Chanel, for being drunk. Sarah and Jill, for being out after dark. Nicole and Bibaa, for being in a park. Despite how far we’ve come in the fight for women’s rights, this means it’s still almost always women having conversations and taking measures to prevent ourselves, our friends and women we don’t know from being raped or murdered by men.

Women were at the forefront of organising Sarah’s virgil. Women were the ones speaking on the news about what needs to change, and the ones writing the op-eds that were widely shared online (by other women). Though my Instagram feed was full of posts about Sarah’s death, not one of them was shared by a man.

A quote widely shared in the wake of Sarah’s murder, originally said by Jackson Katz during a 2013 Ted Talk reads, “We talk about how many women were raped last year, not about how many men raped women. We talk about how many girls in a school district were harassed last year, not about how many boys harassed girls … even the term violence against women is problematic. It’s passive construction. There’s no active agent in the sentence. It’s a bad thing that happens to women. It’s a bad thing that happens to women, but when you look at that term violence against women, nobody is doing it to them. It just happens. Men aren’t even a part of it!”

Instead of us caveating all stories about violence against women with a ‘not all men’ line to avoid bruising men’s egos and resulting backlash about angry, men-hating feminists, we should instead focus our language on shining a spotlight in the direction of the source of the problem. When nine out of 10 murderers sentenced in the past decade in the UK are men and 98.5 percent of convicted rapists are men, there’s no denying that source is overwhelmingly, you guessed it: men.

Here, using active language can be a political act. Asking the question: ‘How many men raped women?’ rather than ‘How many women were raped?’ is much more likely to lead to actions that prevent rape because it puts the onus of responsibility on those who engage in abusive behaviors. It focuses on the cause, rather than on the victim. It forces all men—even if they aren’t murderers and rapists—to join the conversation.

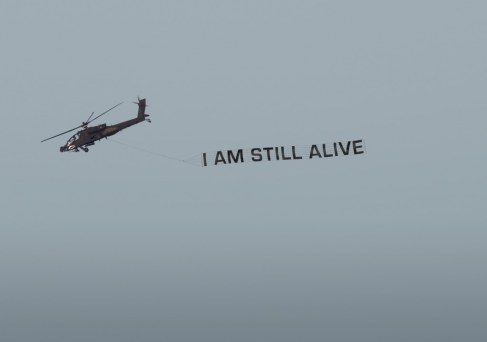

In the wake of Sarah’s death, the British police force announced two immediate changes: more lighting on the streets and more CCTV footage. In response, women everywhere rolled their eyes. The focus shouldn’t be on needing to capture these violent acts on camera, it should be on preventing them from happening in the first place. But if we change the way we speak about an issue, the way we respond to it will change too. Perhaps next time a young woman’s life is tragically taken, we’ll say ‘it was a man committing violence’, instead of ‘violence against a woman.’ Perhaps then the conversation will surround why a man thought he had the right to end a woman’s life after dark, instead of why she was out after dark at all.

__

SIDE-NOTE acknowledges the Eora people as the traditional custodians of the land on which this project was produced. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reading this.