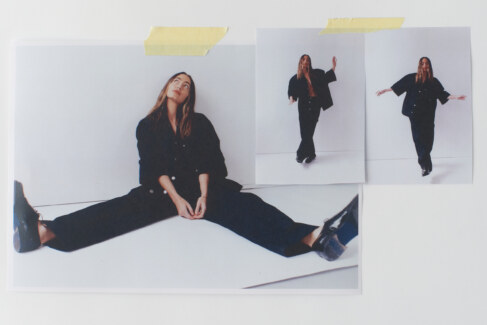

Phillip Keir by Nathan Harrandine-Hale

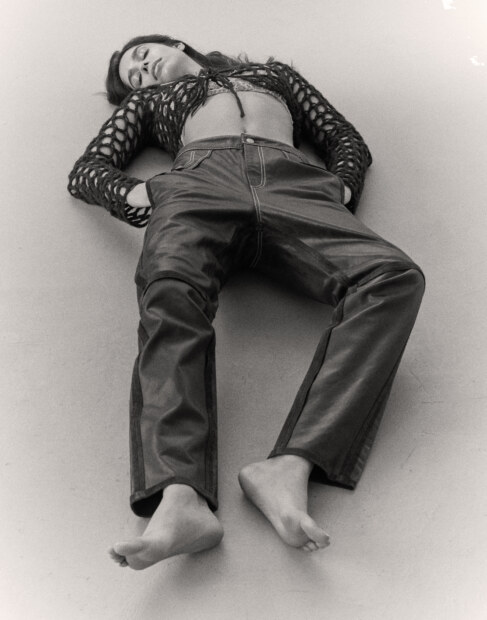

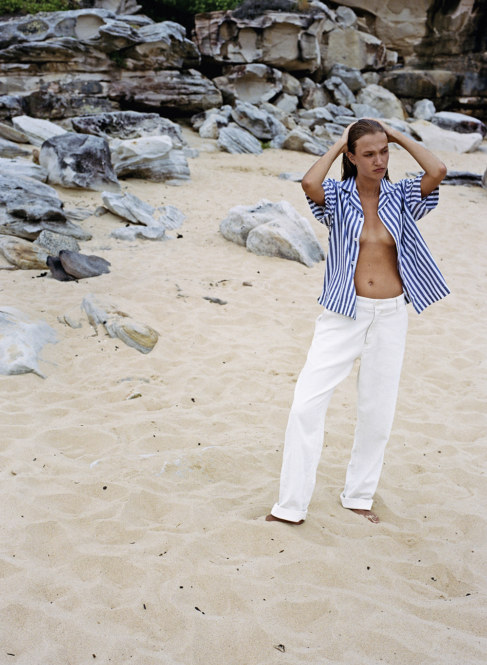

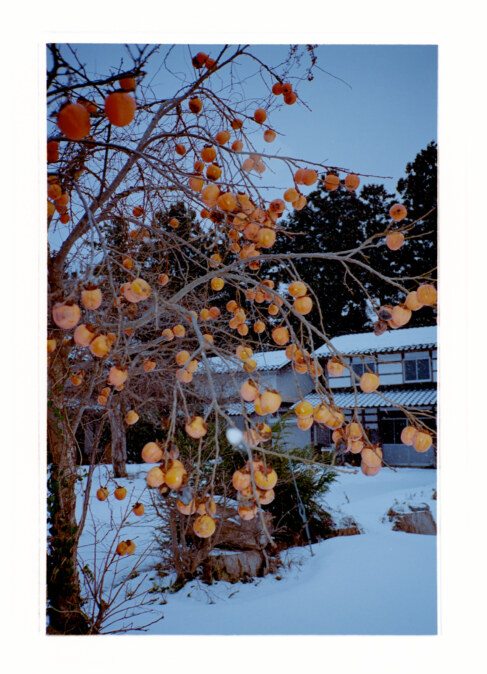

THIS MUST BE THE PLACE BY SOPHIE DONALDSON & NATHAN HARRADINE-HALE

WRITTEN AND PRODUCED BY: Sophie Donaldson

PHOTOGRAPHED BY: Nathan Harradine-Hale

DESIGNED BY: Francesa Nwokeocha

Imagine a building that, over the course of nearly a century, has been a place of firsts for the city in which it resides; first bookshops, first bistros, first bars. It’s a beautiful building too, one of a pair designed by esteemed architect John Sulman and modelled on Florence’s 15th-century Foundling Hospital. The Sydney and Melbourne Buildings, with their Roman tiled roofs, sweeping loggias and graceful colonnades are something of an anomaly in Canberra, given it’s a city famed for neither heritage architecture nor a thriving social scene. In the walls of these landmark buildings you’ll have found both, at one stage or another.

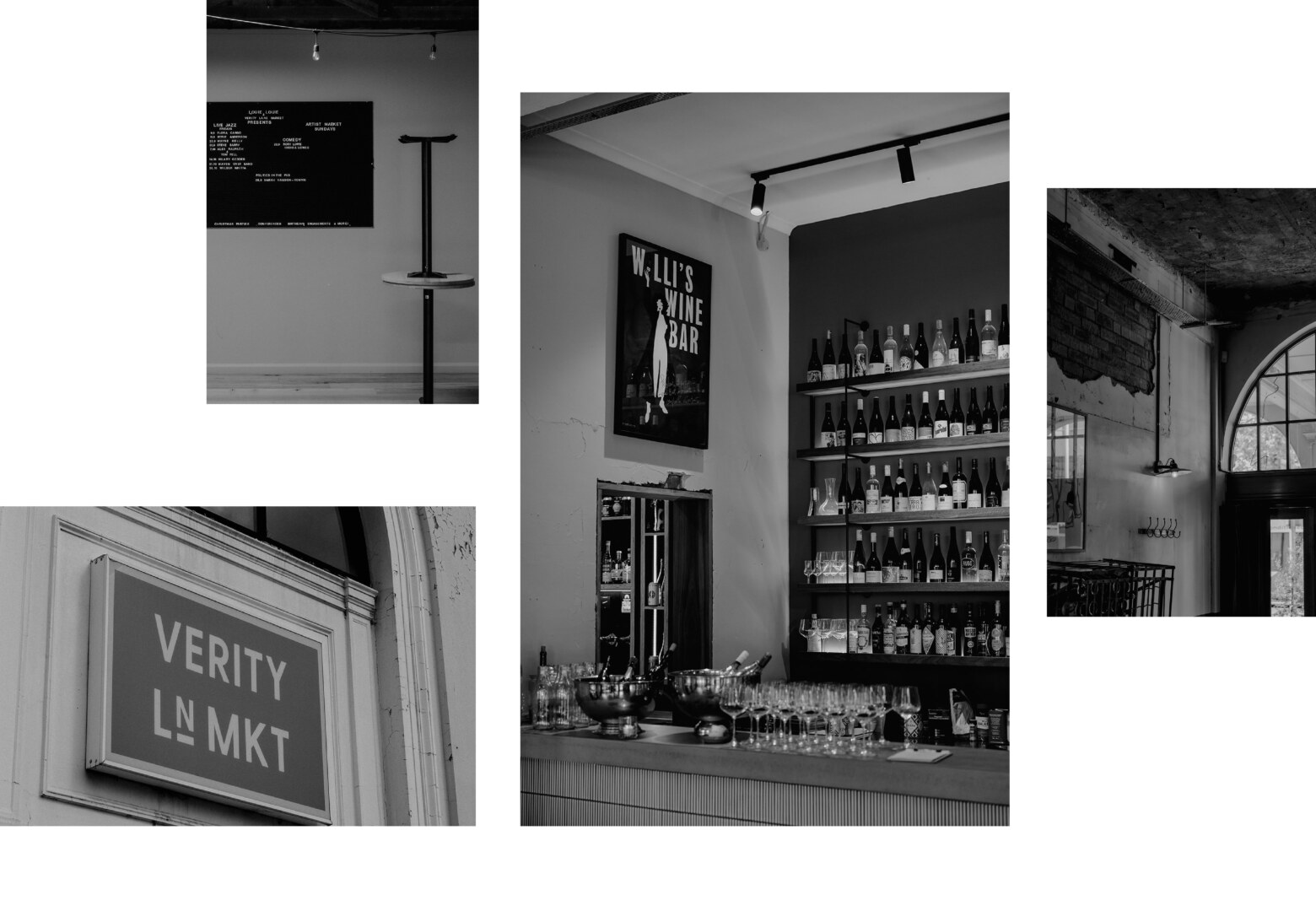

In the mid-aughts the city’s student population would cluster around the Brunelleschi-inspired Sydney Building, bar hopping from one venue shilling $2 shots to another. Before this, Private Bin was the nightclub-cum-comedy venue frequented by a motley mix of students, politicians and public servants. And before this, the building was inhabited by a cluster of independent retailers, giving the civic centre an air of a bustling market town. Despite its landmark status the building has been described in recent times as a collection of ‘tired, tatty and erratic façades’, a legacy of the piecemeal approach to its construction that has plagued it from the beginning. Despite this Phillip Keir, a former theatre director and erstwhile publisher of Rolling Stone in Australia, saw potential in the grand old dame. Over the course of six years, Keir and his team reimagined his portion of the Sydney Building and its accompanying laneway. The result is Verity Lane Market, a beautifully restored section of the building that houses a food hall, several bars and an upstairs space that hosts cultural events and performances. Most notably Keir flipped the orientation of the building by installing the venue’s entrance in what was formerly an unloved laneway.

“A lot of people told me it just wouldn’t work because you can’t park there first of all, so families wouldn’t go, and it was dirty and dangerous. I had to prove it would work, and as we went we decided what we would do with other parts of the building,” he recalls.

“Upstairs we have a space that can be used as seating for the food hall, but it’s also a performance venue. We have lots of talks, book launches, jazz, sometimes theatre. Canberra people are very interested in ideas. Politics is of course one of the local industries so a lot of people know who’s doing what.”

Verity Lane Market, which takes its name from Verity Hewitt, the owner of the city’s first bookstore located in the Sydney Building, has been a runaway success and could serve as a blueprint as to how the city might develop its historic buildings and urban centres. The venture is Keir’s first in development and restoration and the most recent project in a career that spans the arts, philanthropy and publishing.

Aged twenty, he left Sydney for 1970s Manhattan, a period defined by both an escalating crime rate and an influx of artists who took advantage of the cheap rent and empty buildings left behind by those fleeing for the relative safety of the suburbs. It was a hotbed of creativity and gave rise to era-defining artists like Patti Smith, Lou Reed and the New York Dolls, and Keir was in the thick of it. He began dancing and then interned with the legendary experimental theatre company The Wooster Group, an experience that would seed in him a lifelong passion for performing arts.

“South of 14th Street became the thing and that’s where all the dance and visual arts people were. There wasn’t a big commercial industry at that time. It was very un-siloed, so even if you worked in dance you could collaborate with other performers and people would move back and forth between disciplines all the time,” he reflects.

“I performed at The Kitchen, it’s actually the favourite thing on my CV. I had just turned 21. The Kitchen was one of these arts places that did a lot of early video art for instance, but it was also where the Talking Heads played for the first time.”

Still in his twenties, Keir left for London where he spent six years working in theatre before landing in Cologne, Germany. Immersed in experimental theatre-making, he returned to Australia where he took up a post with the Sydney Theatre Company as both a director and a dramaturg, working on the text of productions and translating scripts from playwrights such as Bertold Bretch.

With a decade of what he describes as ‘high culture’ under his belt, he turned to publishing. In 1987 Keir, along with Toby Creswell and Lesa-Belle Furhagen, whom he was married to at the time, pitched for the Australian licence of Rolling Stone magazine, pitting themselves against established publishing corporations also vying for the opportunity.

“We were the Steven Bradbury of publishing because everyone else involved fell over. We shouldn’t have got it but we were the only ones left standing. Fairfax Media were keen to get it but one of the family members wanted to take over, so all the corporate activity had to stop. They had to pull out. The other main bidder was a large radio company. It just so happened that the American general manager (of Rolling Stone) hated radio people; he had just been sacked by a radio person… so he just discounted them, even though they had lots of money, which we didn’t. We had to scrape together our deposit,” he recalls.

The late eighties ushered in a prolific period in Australian music which in turn propelled the popularity of publications like Rolling Stone.

“In the sixties and seventies the charts here were dominated by UK and US releases. Then there was a period when a whole lot of local music came along and suddenly half the top ten was Australian, which had never happened before,” he recalls.

“Because Rolling Stone was an existing title we had cache to work off. It was a very well edited and structured magazine and it was how I learnt about publishing, it was a great training ground. Because of this upsurge in music there was an underswell of small music newspapers. Rolling Stone was written off a bit because it was seen as American so our job was to Australian-ise it. We were just lucky at that time there was a lot of material to work with. We reduced the amount of American material and replaced it with local content.”

It was the “golden era of Darlinghurst,” he remarks, and the small team immersed itself in the cut and thrust of music journalism as well as the rollicking live music scene taking over Sydney. They founded Next Media and went on to publish twelve titles with a staff of seventy. In 2008 Keir, by then the sole owner, sold Next and returned to his roots as a performance artist, this time side of stage. He founded the Keir Foundation, a philanthropic arts foundation that awards grants to theatrical and dance productions. He also sponsors the Keir Choreographic Award, a national prize that promotes and develops new choreography.

Along with his philanthropic work Keir is continuing his foray into property and sees Verity Lane Market as an ongoing project. Despite Canberra’s status as a young city, he is drawn to its heritage architecture.

“I really like the old side of Canberra. As far as I could see some developers would avoid heritage, because there are restrictions on what you can do of course. But I thought the opposite, that the Sydney Building presented an opportunity for something different, rather than everything being new,” he says.

“There has sometimes been an attitude in Canberra of ‘knock it down and start again’; I think partly because Canberra started as a temporary town and they had to literally build things so quickly, because there was always a shortage of accommodation, office buildings and so on. Even the first Parliament House was built as a temporary building with the main one built later. There has always been a sense of temporary-ness, the idea that we’ll build something first and after that we’ll build the real thing.”

It is the people that maketh the place, and all that, but the people of a city need a place to go; in Canberra, that place can be found down a laneway and up the stairs of an old building made new again.

_________

SIDE-NOTE acknowledges the Eora people as the traditional custodians of the land on which this project was produced. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reading this.