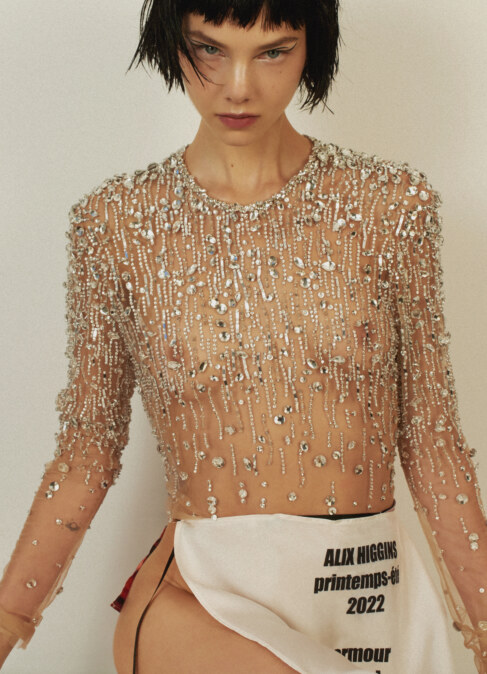

MADE UP BY DEREK HENDERSON AND MATILDA DODS

PHOTOGRAPHED BY: Derek Henderson @ M.A.P

HAIR AND MAKEUP: Victoria Baron @ M.A.P Using Nars @ Mecca

MODEL: Tatyana Gillam @ Modules Management

WRITTEN BY: Matilda Dods

In her canonical book “The Beauty Myth”, Naomi Wolf writes ‘the ideology of beauty is the last one remaining of the old feminine ideologies that still has the power to control those women whom 2nd-wave feminism would have otherwise made uncontrollable.’ Wolf concisely makes the double-pronged point that despite the progress of the preliminary feminist movements, we as women are still controlled by the ideologues of traditional beauty standards, that perhaps without, women may become truly uncontrollable. I do not agree with Naomi Wolf.

I believe that beauty, and the ways in which women and men play and interact with it, has become a spectacularly uncontrollable force. The combined effects of globalisation and digitalisation has loosened the choke-hold grip of conventional beauty standards around expressions and understandings of beauty and identity. Beauty as a form of self-expression, as a sign of liberation, has traditionally been scorned or discredited by both certain feminist discourses (*cough, Ms Wolf) and mainstream media alike. Coupled with this is the continuous antagonisation of frivolity, or things indulged in purely for fun.

Guilty pleasures are continually delegated to the cultural Siberia of ‘low-culture.’ These activities are also continually coded as feminine. Investment in beauty, in make up, in watching ‘trashy’ youtube tutorials, in a new sparkly eyeshadow for the hell of it, can function as a gestural fuck you to the conventions that discredit the revolutionary potential of frivolity. Make up, and the beauty industry when subtracted from narratives of both mass consumerism, and oppressive beauty standards, contains the potential for rebellious lightheartedness. The personal is political, but that does not mean that either can’t be fun. The new identity of the beauty industry is fun, embracing its inherent frivolity and its revolutionary potential as a political force.

Embedded within this argument is the cultural conception of high and low culture, and the cultural capital that is acquired and transferred through investments in these cultures. Despite being a multi-billion dollar industry, giving beauty you-tubers and influencers the potential to earn up to $100,000 per post or video, the beauty world is still decidedly delegated as low-culture. Watching beauty tutorials or investing in new beauty products is classified as a ‘guilty pleasure’; reprehensible indulgences for the superficial – whilst high culture, watching a documentary or reading a book that you feel smug about having left out on your coffee table, are held in some higher kind of cultural esteem. Following this is the conception that one cannot be invested in both simultaneously. Smart girls like books, dumb girls like makeup. Resisting the binary dictating that ‘smart girls’ don’t like those things, offers myriad possibilities for new forms of self-expression and understandings of femininity. That girliness is delegated to low-culture, something to be ashamed of, or thought of as a guilty pleasure, only functions as a tool to both discredit frivolity and femininity. Why should I feel guilty about the things that make me feel good, when largely men do not face the same kinds of repercussions? Why should I feel guilty about spending $50 on a new concealer, or an hour spent learning how to execute the perfect cat-eye if at the end of it I am genuinely uplifted, and had fun doing it? Through the celebration and appreciation of frivolity, women are offered an opportunity to say fuck you to the structures and discourses that discredit them.

Wolf’s statement, regarding the beauty industry as the final remnant of ‘old feminine ideologies’, ignores both the myriad forms of self expression and creativity that are offered by the beauty industry, and ignores women’s agency and awareness of the structures and discourses within which any practice exists. It is undeniable that oppressive beauty ideals exist, awarding incredible amounts of privilege to those that can perform them successfully. Despite being inscribed with these structures, we are not however, wholly subscribed to them. Consumers are able to see and identify the powers and narratives at work in the industries and media they consume and the products that they buy, and are therefore able to critically respond and reshape these structures.

As all industries are continually digitalised, the gap between producers and consumers is becoming smaller, allowing for more effective communication of the requirements of the consumers. Consumers of the beauty industry, myself included, no longer want to be sold products on the basis of curing some kind of deficiency, and simultaneously pushing back against cultural narratives which propose that participation or investment in the beauty industry is a hapless and silly endeavour. Brands such as Glossier and Fenty Beauty have both torn up and thrown out the playbook when it comes to creating and advertising their products. Focusing on make up, that at its core is fun and as simple as you want it to be. Increasing representation and conversations about diversity within the industry are creating spaces for multitudes of new identities, bodies and experiences. In cases such as this, we vote with our money, and when consumers support brands that are rewriting the rules, we are ourselves pushing back against the historically prescribed version of beauty that is sold to consumers, and demanding genuine and productive representation.

Social media has also offered the opportunity for individuals who previously existed purely as cultural consumers to become cultural producers. It has provided a platform wherein anyone can create and express myriad new identities through self-curation and media production. A selfie, pejoratively viewed as a narcissistic act, in fact contains an immense amount of disruptive power. Assuming access to a smartphone and the internet, anyone, regardless of age, gender, subscription or non-subscription of normative beauty ideals has the ability to take and post a selfie. Self-representation and self-curation online exists in opposition to and alongside advertising which dictates that only certain images and kinds of beauty are culturally proliferated. Again, the revolutionary potential of a frivolous act is concealed through its coding as feminine, low-culture and superficial. The intersection of the beauty industry, digitalisation and self- representation offer a plethora of new perspectives and representations of beauty that are created and dispersed by the consumers themselves. Is this not a truly uncontrollable force?

No industry is perfect, and the beauty industry is far from it. And it may have its roots in old feminine ideologues which sought to control or restrict women. Today however, it offers a space wherein women can control their own representations as opposed to being controlled. The expansion and diversification of cultural production through social media allows for an increasing awareness, consideration and alternatives to traditional narratives of beauty. Following this, I believe that embracing a rebellious frivolity when it comes to interacting with the beauty industry and its associated practises provides a new lens through which to consider the nature of high and low culture and the rejection of such structural binaries. Beauty is an incredibly powerful cultural force, offering innumerable opportunities for self expression and self- representation, and when there is space made for it – it becomes a truly uncontrollable force.